Hello Story Matters readers, hope life is being kind to you this week. If you’re a new sign-up here, then this is my newsletter for readers, where I share my news, book recommendations etc., and write pieces on contemporary culture.

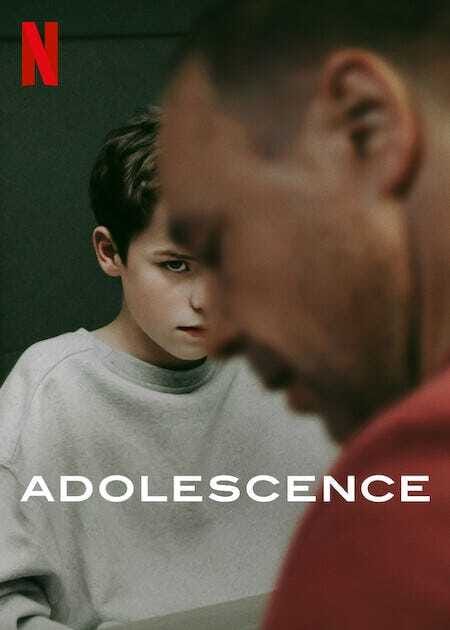

Today I’m taking a look at the 2025 Netflix hit Adolescence, and I’d love to know your thoughts after reading…

Have you watched Adolescence yet? This incredible, gritty Netflix sensation, released earlier this year and recently nominated for a slew of Emmys, has been sparking a wide and essential cultural conversation.

It’s the story of 13-year-old Jamie Miller, who’s accused of stabbing a girl after being influenced by incel culture (involuntary celibate), which encourages men to blame women for their lack of relationships and opportunities. Told through four set pieces (using remarkable continuous camera shots in the one-hour episodes), the show highlights the moment of arrest, the reaction at school, Jamie’s meeting with a psychologist, and the longer-term impact on Jamie’s parents and sister.

Writer Jack Thorne co-created the series with Stephen Graham, the actor who plays Jamie’s father. Thorne told the BBC that he hopes the drama conveys Jamie’s behaviour as the result of numerous, complicated factors. And yet, because the last episode of the show chooses to focus in on the parents, the final images we’re left with are details of their suffering and self-blame.

In one key scene, Manda Miller (played by Christine Tremarco) says to her inconsolable husband that she thinks it’s okay for them to know they could have done better – should have done better. They discuss specific moments where their actions may have been pivotal in Jamie’s mental decline, detailing very human failings like feeling embarrassed for their child on the soccer field (an event which Jamie also recalls with his psychologist) – not usually the stuff of abusive nightmares. Their self-reflection and willingness to take on some responsibility is admirable, because we all know that they, like all of us, could undoubtedly do better in our children’s lives. However, does the choice to linger on this traumatised family in the final episode leave the viewer with their culpability as the key takeaway? Particularly when the scarier question, for all parents, is the one they didn’t ask:

What if they couldn’t do any better?

They could, of course, have banned technology in their house, and been more aware of the damage it might cause. But any parent knows there’s often uproar at the suggestion of even a reduction in screen time, and that they can’t monitor what their kids are doing for at least half the day anyway, during school. And parents also understand they have to choose between what they believe to be the lesser of two evils at this point in human evolution: refuse to allow their kids the access to the technology and social media that their peers have, thereby making them vulnerable to social isolation; or allow it to creep in, and pray they don’t get bullied or witness too much that’s traumatising, because that is the circuitous route to… social isolation.

There are many nuances here, and modern parents spend a lot of time assessing which apps our kids are safe on and which we want them to avoid, trying to guide them through this technological minefield with no experience of our own in regards to being a teen amidst the onslaught of 24/7 tech. How can we hope to understand what it’s like to grow up in the glare of this inescapable, intrusive, information-seeking Sauronic eye, which lies benignly in our kids hands while its algorithmic guts hunts down their interests and vulnerabilities like a homing missile?

However, where exactly do our responsibilities lie, then, and how do we set about understanding them? I don’t want these to be questions we must intuit from reading subtle meanings into our watching experience. I would rather they were carried like aeroplane banners beneath the drone that moves so seamlessly between one perspective and another in episode three.

Because what if the problem is that all of this bullying and misogyny and peer pressure and latent violence hides like insidious, growing cancers in the complex spaces between school and home, technology and teen slang – everywhere and nowhere at once, the roots unable to be entirely located and therefore pulled out and destroyed.

How do we tackle this? What can we do?

Of course, once the malignancy of Jamie Miller’s experiences and impulses coalesced into his horrific and violent act, he must be held accountable and kept away from society, in order to punish the wrong-doing, get justice for the victim, and keep others safe. I’m not suggesting there is any escaping the individual blame that should be assigned to such horrific choices and actions – but however much we might decide to hold the boy or his parents or his friends accountable, it always feels tempting to pin the causes of a terrible crime on something solid, with flesh and bone, rather than to search for it in the dark spaces we can’t quite yet access.

And we really need to do the hard yards, because parents are already exhausted and frightened about what is happening to our kids. Alarms are being sounded by teachers all over the place that this is the zombie generation: disengaged and unable to put down their phones. Tests are being made easier to accommodate their inability to think deeply. And none of this is the way forward in stamping out the violent behaviours that terrify us.

The tech barons that push back against Australia’s social media bans are not sad because our youth will lose all the wonderful things they offer: they are stressed out about their bottom line and their ability to dominate our culture if we help the next generation to remember to look up.

In an ideal world, we would have more sophisticated and trustworthy apps that have their own limits and would therefore not need these bans – but while we can’t trust that, we have no choice but to work with what we’re given. And what our teens have been given is hyper-access to a continually changing culture and language that judges, victimises, threatens and brutalises at the press of a button. I don’t want to watch two broken parents taking on too much of the blame for that. I’d like to think that beyond that final episode, they also realise the parts they are not responsible for, and use that awareness to push for change too.

Adolescence is one of the best series I’ve watched this year, and I hope it wins all the awards it deserves. Nevertheless, our society moves at warp speed, and the media focus will inevitably move on quickly. It’s essential that while we’re still talking about this story, we try to drill down into these discussions, for the sake of all women and young girls who live with this lurking threat. Otherwise, after the show’s endeavours to add nuance to a confronting topic, we might still end up missing some of the important, if murkier, parts of this vital conversation.